Physiological and Behavioural Aspects of Extreme Calorie Restriction

Educational content only. No promises of outcomes.

Adaptive Thermogenesis Explained

Metabolic Rate Reduction Mechanisms

When the body experiences severe caloric deficit, metabolic adaptation occurs—a physiological response where the body reduces energy expenditure below what would be predicted based on body weight alone. This process involves multiple hormonal and enzymatic adjustments that lower thermogenesis (heat production) and reduce activity-dependent energy expenditure. Research demonstrates that these reductions follow predictable patterns based on the magnitude of the deficit and individual characteristics including age, sex, and body composition.

The mechanisms underlying metabolic adaptation include reduced sympathetic nervous system activity, decreased thyroid hormone signalling, and altered mitochondrial efficiency. These changes represent the body's preservation strategy during perceived scarcity and occur relatively rapidly during severe restriction phases.

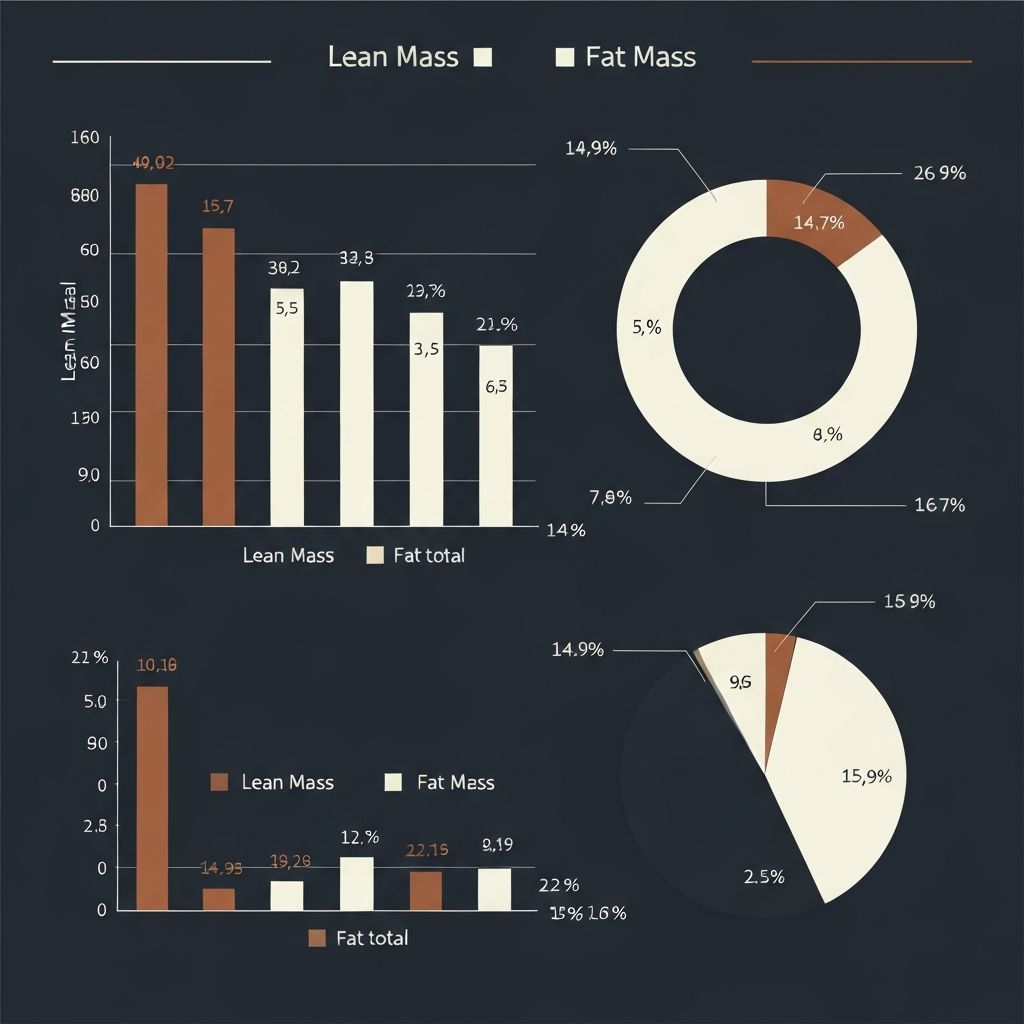

Body Composition Changes in Restriction

Lean Mass Loss During Severe Restriction

During extreme caloric restriction, weight loss comprises both lean tissue (muscle, organ, bone) and adipose tissue. The proportion of lean mass loss increases with the severity of the deficit and duration of restriction. Research from metabolic ward studies demonstrates that very low-calorie diets (below 1200 kcal/day) typically result in lean mass losses of 25-35% of total weight loss, considerably higher than more moderate deficits where lean mass comprises 15-25% of weight loss.

Lean tissue losses reflect both reduced anabolic signalling and increased catabolic hormonal environments. Inadequate protein intake, micronutrient deficiencies, and the metabolic signalling induced by severe restriction all contribute to preferential lean tissue mobilisation. These changes have functional implications for strength, metabolic capacity, and recovery patterns post-restriction.

Hormonal Responses to Severe Deficit

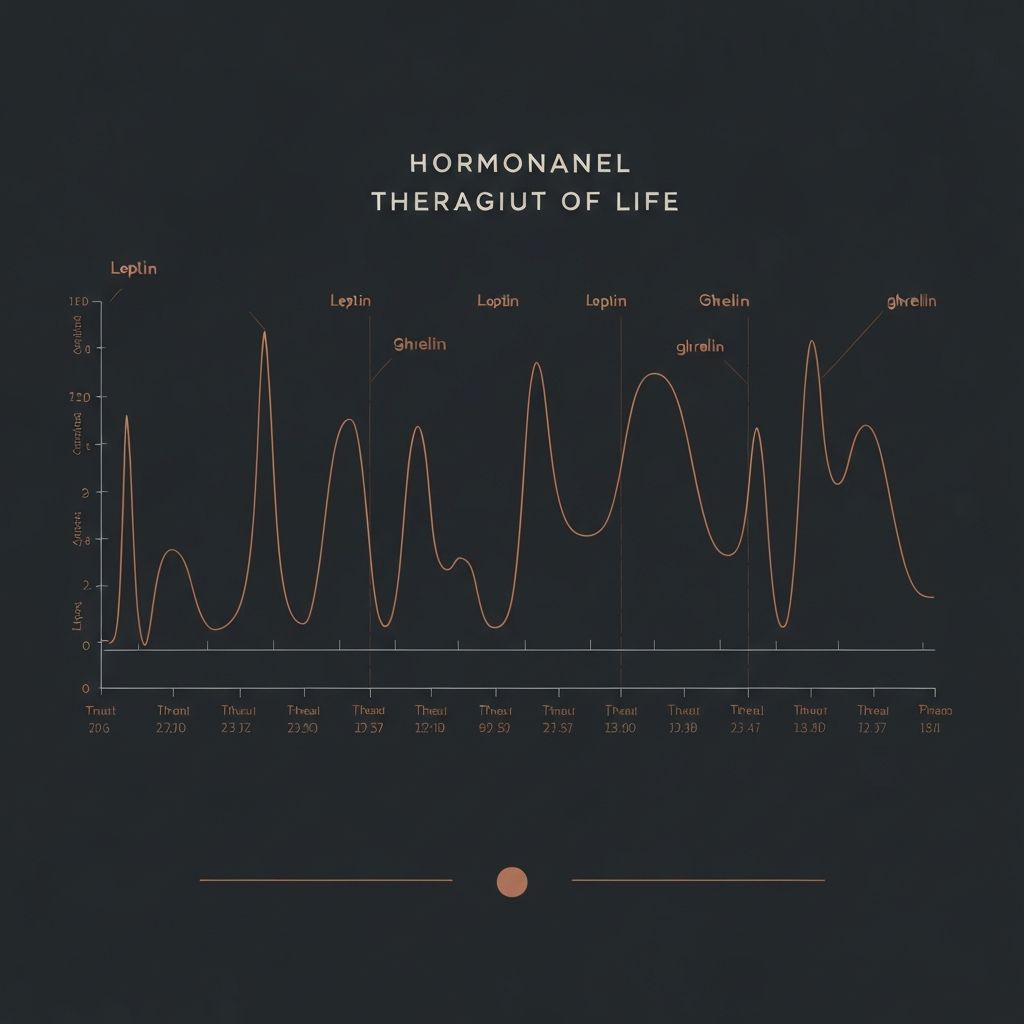

Leptin, Ghrelin, and Cortisol Dynamics

Severe caloric restriction produces characteristic hormonal responses. Leptin, a hormone that signals energy status to the brain, decreases in response to low energy availability. Even modest weight loss triggers leptin decline, which initiates compensatory increases in appetite-related neural signalling and reduced satiety signalling. These changes promote increased food-seeking behaviour and reduced feelings of fullness.

Ghrelin, the primary appetite-stimulating hormone, increases during restriction and remains elevated until energy balance is restored. Cortisol, the primary glucocorticoid hormone, also tends to elevate chronically during sustained restriction as part of the metabolic adaptation response. Together, these hormonal shifts create a neurobiological environment that strongly favours increased energy intake once restriction ends, a factor in observed weight regain patterns.

Psychological Effects of Extreme Restriction

Extreme dietary restriction triggers consistent psychological responses documented across research contexts. Increased cognitive preoccupation with food, eating thoughts, and food-related planning becomes nearly universal during severe restriction. This phenomenon reflects both physiological signalling from energy deficit and the psychological demands of strict dietary adherence.

Disinhibition—a loss of restrained eating control—occurs frequently during and after restriction phases. Research demonstrates that dietary restraint itself may sensitise individuals to disinhibition when strict rules are violated, creating vulnerability to periods of overconsumption. Additionally, sustained restriction often produces mood changes, reduced social flexibility around food, and difficulty with food-related decision-making even in non-eating contexts.

The psychological burden of extreme restriction contributes significantly to adherence difficulties and high dropout rates in very low-calorie diet research. These effects reflect normal neurobiological responses to caloric deprivation rather than individual weakness or failure.

Nutrient Deficiency Risks in Extreme Approaches

Extreme caloric restriction necessarily limits total nutrient intake, creating risk for multiple nutrient deficiencies even when food selection is carefully considered. Micronutrient requirements remain relatively constant across different caloric intakes—a principle that means severe restriction inevitably concentrates the diet, reducing variety and micronutrient density.

Very low-calorie diets frequently result in inadequate intake of iron, zinc, B vitamins, calcium, and several essential amino acids. Protein requirements, expressed as grams per kilogram of body weight, actually increase during caloric restriction to maintain lean tissue, yet total protein intake often decreases due to low overall food consumption. These deficiencies can impair metabolic function, immune response, and tissue maintenance during restriction.

Micronutrient status also influences metabolic rate and energy expenditure through multiple enzymatic and mitochondrial processes. Deficiency states may amplify metabolic adaptation and impair recovery of metabolic function during refeeding phases.

Water and Glycogen Fluctuations

Short-Term Versus Sustained Changes

Initial rapid weight loss during the first week of extreme restriction reflects primarily water and glycogen depletion rather than fat loss. Glycogen, the stored form of glucose in muscles and liver, is depleted relatively quickly during caloric restriction, particularly during combined restriction and exercise. Glycogen depletion triggers secondary water loss, as glycogen storage requires 3-4 grams of water per gram of glycogen stored.

This rapid initial loss often exceeds 2-3 kg in the first week, creating psychological reinforcement for continuing restriction. However, these changes are largely reversible through normal eating patterns. True adipose tissue loss progresses more gradually, following predictable relationships with caloric deficit magnitude. After glycogen stores are normalised, weight fluctuations become smaller and more stable, reflecting actual changes in body fat and lean tissue.

Understanding these distinct phases clarifies why initial dramatic weight loss does not predict longer-term outcomes and why weight regain patterns following restriction termination include rapid water and glycogen reaccumulation.

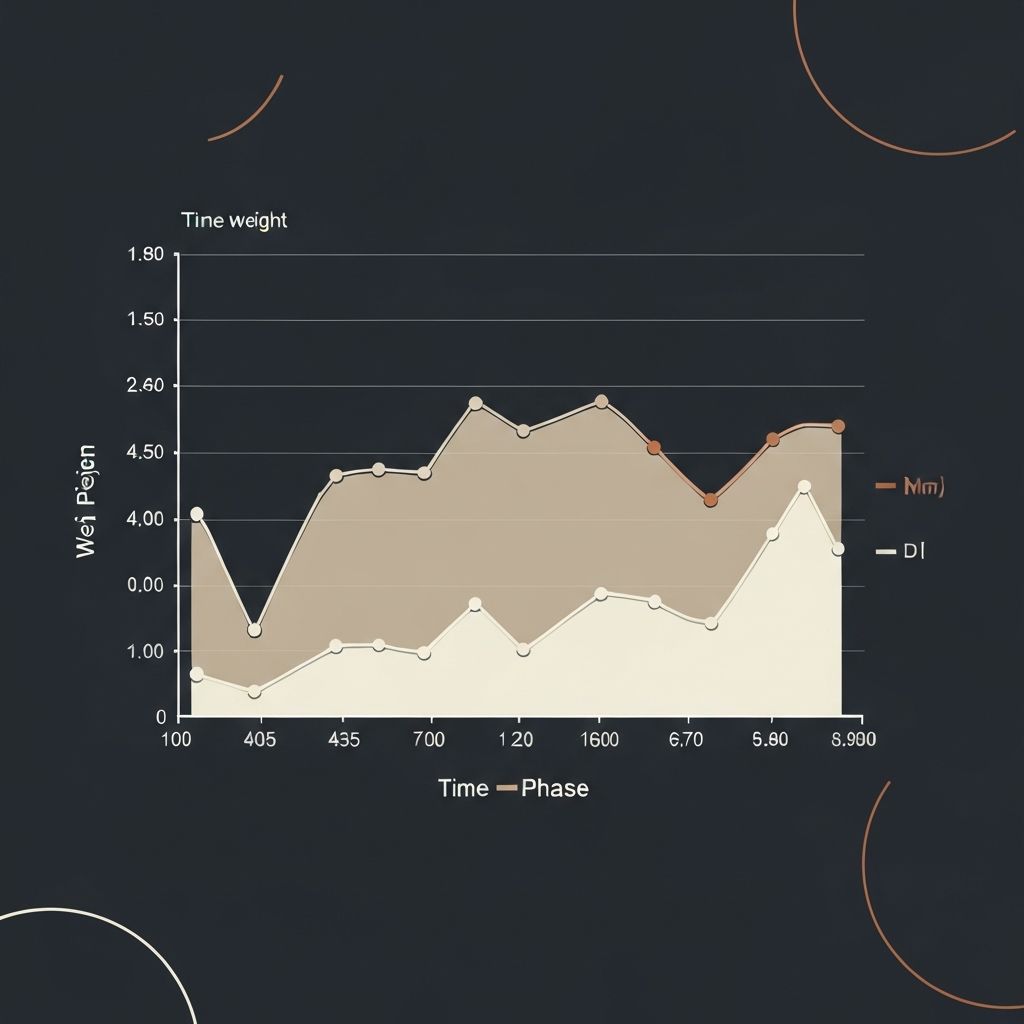

High Regain Patterns in Research

Long-term follow-up studies of individuals completing very low-calorie diets consistently document high rates of weight regain. Research indicates that 50-80% of lost weight returns within 2-5 years post-intervention, with many individuals reaching or exceeding initial weight within 5-10 years. These patterns are not unique to extreme restriction but become more pronounced with greater initial weight loss and greater caloric deficit magnitude.

Regain reflects multiple converging factors: persistent metabolic adaptation, altered hormonal signalling, acquired disinhibition patterns, and return to pre-restriction eating behaviour. The magnitude of regain often exceeds the maintenance caloric intake that existed before restriction, suggesting that physiological and psychological changes induced by extreme restriction persist longer than the restriction period itself.

Research examining trajectories shows considerable individual variation—some individuals maintain substantial weight loss whilst others experience complete regain. This variation relates to factors including genetic predisposition, sustained behavioural changes, and individual responsiveness to metabolic adaptation.

Metabolic Ward Study Insights

Controlled metabolic ward studies provide the most precise data on physiological adaptation during extreme restriction. In these settings, food intake is strictly controlled and measured, physical activity is monitored, and body composition changes are precisely quantified through methods like dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). These studies eliminate behavioural confounds present in free-living research.

Key findings from metabolic ward research include: metabolic adaptation magnitude correlates predictably with deficit severity; lean tissue loss increases with deficit magnitude and restriction duration; hormonal changes follow consistent patterns across individuals; and refeeding produces rapid metabolic rate recovery in some dimensions but delayed recovery in others. These studies establish that observed patterns reflect primarily physiological responses rather than behavioural confounds.

However, metabolic ward findings may underestimate real-world adherence difficulties and psychological effects, as controlled environments remove social, environmental, and psychological pressures that influence behaviour in normal living conditions.

Individual Adaptation Variability

Whilst metabolic adaptation follows predictable average patterns, considerable individual variation exists in adaptation speed and magnitude. Some individuals show substantial metabolic rate reduction relatively rapidly during restriction, whilst others demonstrate slower adaptation over weeks to months. This variation relates to multiple factors including genetic characteristics, baseline metabolic state, sex, age, body composition, previous dieting history, and individual differences in adaptive response capacity.

Sex differences in metabolic adaptation merit particular attention—research demonstrates that women tend to show greater metabolic adaptation during caloric restriction compared to men, potentially reflecting both hormonal and metabolic differences. Prior history of restrictive dieting appears to accelerate metabolic adaptation in some individuals, suggesting that repeated cycles of restriction may enhance the body's adaptation response.

Age-related differences also emerge in adaptation patterns, with older individuals sometimes showing greater metabolic suppression during restriction compared to younger individuals. These individual differences underscore that population averages may not accurately characterise any single person's physiological response to extreme restriction.

In-Depth Analysis: Explore Related Research Findings

Adaptive Thermogenesis in Severe Restriction

Detailed exploration of metabolic rate reduction mechanisms including hormonal signalling and mitochondrial efficiency changes.

Read Article →

Lean Mass Loss During Very Low-Calorie Periods

Examination of body composition changes, factors influencing lean tissue loss ratios, and functional implications.

Read Article →

Hormonal Adaptations: Leptin and Ghrelin Dynamics

In-depth analysis of appetite hormone changes, neurobiological effects, and implications for appetite regulation.

Read Article →

Psychological Consequences of Extreme Dietary Limits

Comprehensive review of cognitive, emotional, and behavioural effects documented during and after severe restriction.

Read Article →

Patterns of Weight Regain After Restriction Phases

Analysis of regain trajectories, individual variation, and physiological factors influencing post-restriction outcomes.

Read Article →

Individual Differences in Metabolic Response to Deficits

Exploration of factors creating variation in adaptation patterns across populations and implications of individual differences.

Read Article →Frequently Asked Questions

Continue Exploring Metabolic Adaptation Topics

Browse our detailed articles for in-depth explanations of specific physiological processes and research findings related to extreme dietary restriction.

View All ArticlesEducational content only. No promises of outcomes.